What does better hearing mean to a hearing scientist?

Understanding the relationship between user and product is important when advancing hearing and fitting solutions. Find out more from hearing scientists at Sonova.

Think about this statement:

As hearing scientists, we have done our job developing hearing aids when speech is clearly understood with good sound quality.

Do you agree with that? Is that a sufficiently clear description of the goal of aided hearing? Or can we give a little more precision on the definition of ‘hearing made better’?

Michael Boretzki, Principal Expert Fitting Performance at Sonova, and I have been interested in these questions for a long time now. We need good answers because we want to advance hearing and fitting solutions.

We need to know what to improve, just as you need to know how to do better in clinical practice, right?

Our inspiration: understanding how we can do better

We stumbled upon an excellent paper by Marc Hassenzahl: “The Thing and I: Understanding the Relationship Between User and Product“.

Hassenzahl says that the value of a product for a user has a pragmatic and a hedonic side.

Pragmatic means how well the product is serving the purposes of the user. Hedonic means how much you as a user like the product. This pair of hedonic and pragmatic aspects helps us to concisely say what better hearing means for hearing aid wearers.

The pragmatic side of better hearing

This is how well hearing serves the momentary activities of the user in the current situation. When you are having a conversation, the pragmatic side of hearing is how well it serves the conversation. When you are crafting wood with a tool, hearing needs to serve this activity. If you are listening to music, this is the purpose of hearing.

And, in general, all of us have an interest in staying aware of our surroundings, even if we are deeply immersed in an exciting novel.

Can we identify the essential aspects of hearing abilities that serve us in different listening situations? Clearly, we can:

- Detecting sounds

- Distinguishing sounds

- Localizing sounds

- Recognizing sounds

- Understanding sounds (in a particular soundscape)

Most often we are completely unaware of how well these 5 abilities work for us in the many different environments and situations we are in everyday, because this happens automatically without effort.

If we want to capture them, we need to apply performance measures such as intelligibility tests, localization tests, discrimination tests and audibility tests.

The hedonic side of better hearing

Do we like how we hear? If you are lucky and have healthy ears most often you have no idea about liking or disliking how you hear. Hearing happens automatically, without any real effort.

Your attention is on what you hear but not about the process of hearing itself. If you have a hearing loss and have started to use hearing aids, you are in a completely different world. You know that what is heard can sound strange, unfamiliar, or unnatural.

With loud sounds you could have had moments which were nearly painfully loud. And you could have been in situations in which you were a bit disappointed about the hearing issues which persist despite hearing aids. Not all hearing situations become super easy.

Can we identify the essential aspects that satisfy the hedonic side of hearing? Yes, we can:

- Ease of hearing

- Loudness comfort

- Familiarity of hearing

The proper metrics for the hedonic aspects of hearing are experiences measures, e.g. rating scales.

Did you see the connection?

The five pragmatic and the three hedonic aspects are not independent. They are very concrete aspects of hearing in a particular hearing situation. A hearing situation is understood as a soundscape (which always is connected to an environment) in which you do something and want something in the broadest sense of these words.

So ‘good speech intelligibility with good sound quality‘ is a highly incomplete and superficial way of saying what better hearing is.

We would prefer this: Better hearing is a profile of hedonic and pragmatic hearing advantages of aided hearing compared to unaided hearing – across all relevant hearing situations of hearing life.

When the user is satisfied with this profile, we believe we have advanced our hearing aid and fitting solutions.

Reference

Hassenzahl, M. (2005). The Thing and I: Understanding the Relationship Between User and Product. 10.1007/1-4020-2967-5_4.

Co-authors

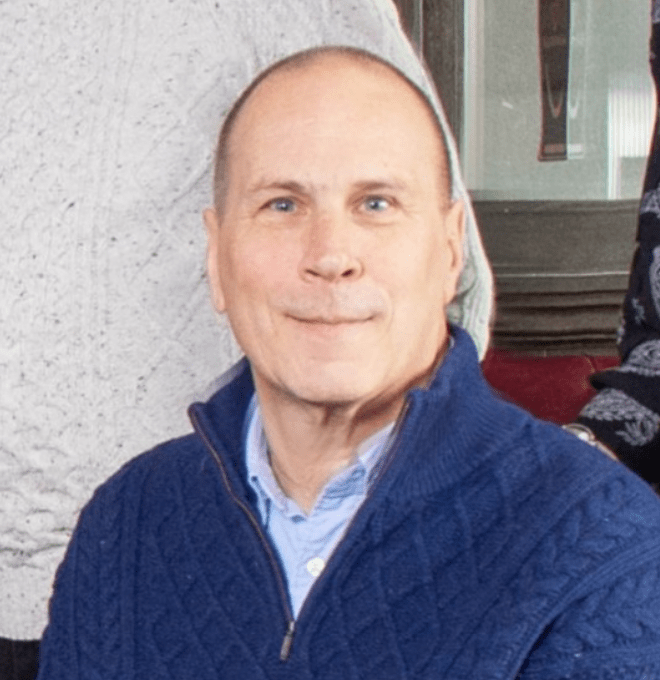

Leonard Cornelisse, Senior Hearing Scientist and Manager of the Hearing System Engineering group, Canada

Leonard has over 30 years of experience in the field; as a clinical audiologist, a research audiologist and in industry. During his time as research audiologist at the University of Western Ontario, he was a codeveloper of the Desired Sensation Level (DSL) a fitting formula that is particularly popular in pediatric fittings. For the last sixteen years, Leonard has worked for Sonova and currently contributes to Advanced Concepts and Architecture in Product Research and Development.

Michael Boretzki, Principal Expert Fitting Performance at Sonova, Switzerland

Michael received his doctoral degree in psychology (specializing in perceptual psychology and psychophysics) and worked at the Psychological Institute at Würzburg University for ten years. In 1997, he joined Phonak as an audiological consultant and trainer, then worked in Phonak’s Research and Development department developing new fitting software functions. Since 2005, he has managed a research program on fitting methods and audiological measures at Sonova AG.