How to give kids with UHL and AP deficits an advantage in the classroom

Want to help children with unilateral hearing loss or auditory processing deficits hear their teacher’s better? Two recent studies highlight the proven benefits of Roger Focus II.

Did you know that children with unilateral hearing loss (UHL) or auditory processing (AP) deficits can actually outperform their normal-hearing peers in certain classroom situations? It may sound surprising, but recent research shows that with the right technology, these students can gain a distinct advantage when it comes to understanding speech in noisy environments.

Two new studies highlight the significant benefits of Roger Focus II, a remote microphone system that delivers the teacher’s voice directly to the child’s ears. The results? Improved speech intelligibility in noise and at a distance—so much so that these children perform better than their peers without hearing challenges in key listening scenarios.

Let’s look at these studies and explore how Roger Focus II can make a measurable difference for students with UHL or AP deficits.

Study #1 – Children with UHL and Roger Focus II

Having a unilateral hearing loss isn’t a trivial thing. In 2019, an international panel of experts developed a consensus practice parameter to provide guidance on the management of children with UHL.1 This guideline highlights the potential difficulties experienced by children with UHL and offers guidance on remediation and treatment options. A key message from these guidelines is that each child with UHL should have the opportunity for intervention.

A question which goes through our minds when we work with this group of kids is, “Could greater access to speech in the classroom remediate at least some of the educational issues resulting from UHL”?

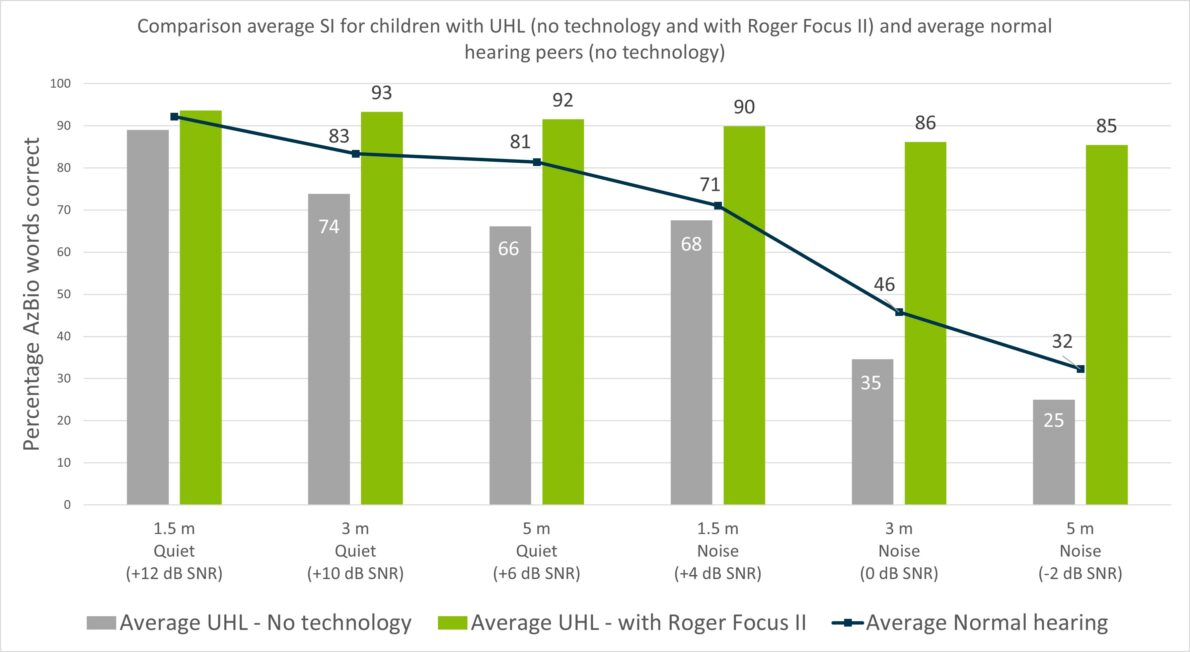

In the Hearts for Hearing study, speech intelligibility was measured with and without Roger Focus II in 16 children with UHL and 10 of their peers (children with ‘normal hearing’). They measured in both quiet and in noise at different distances to simulate different positions in the classroom.2

Here are the results.

We can see from these results that even in a quiet environment, children with UHL are missing out on a lot of the teacher’s speech when they are seated at a distance.

However, using Roger Focus II provides significantly better speech intelligibility for these children compared to using no technology, regardless of whether it is quiet or noisy.

In fact, when using Roger Focus ll in a noisy, simulated classroom, children with UHL understand distant speech, such as a teacher’s, significantly better than their normal hearing peers (an impressive 53 percentage points better at a distance of 5 meters).

Study #2 – Children with AP deficits and Roger Focus II

And, now for the study with children with AP deficits. Researchers at the University of Melbourne focused on speech intelligibility as well as auditory and visual attention. This study was different from others as it measured attention in these children objectively rather than subjectively.

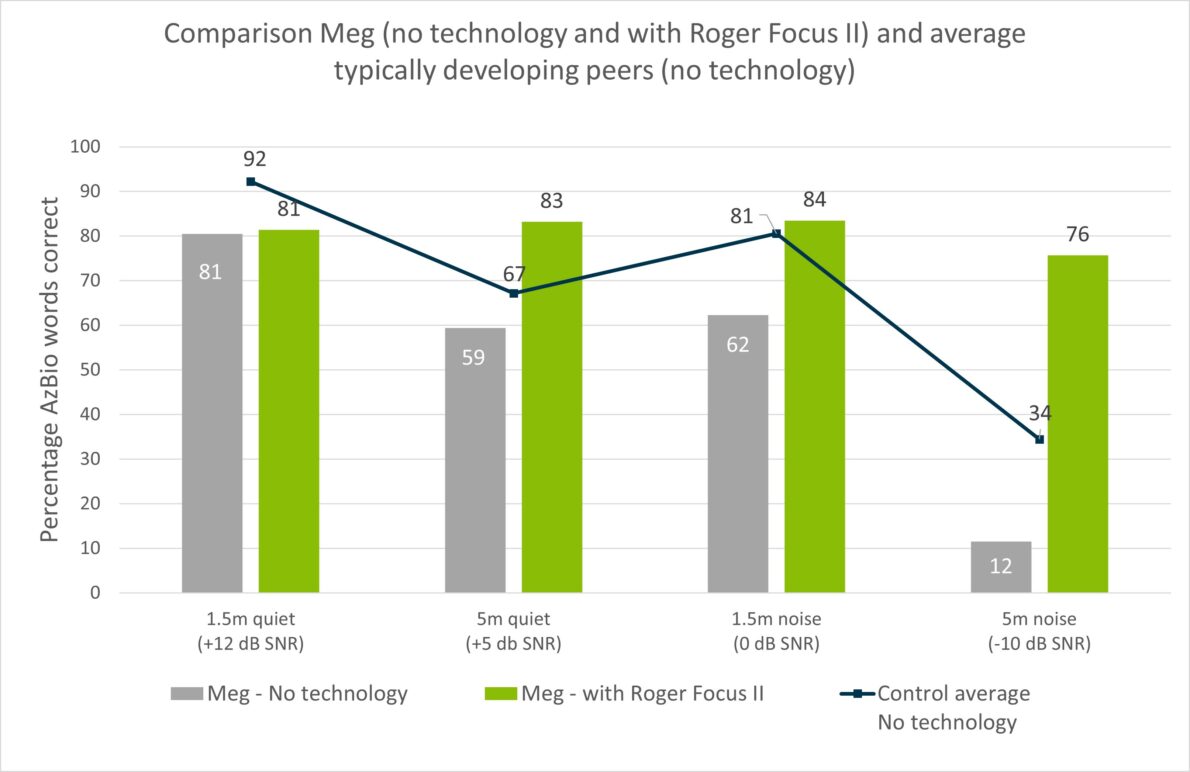

Because the peer-reviewed paper is not yet published, the publication listed below3 used the results for one of the children (“Meg”) with AP deficits that reflected the average of the whole AP deficits group. These results are compared with the average of the control group. The control group was 10 typically developing children with normal hearing thresholds in both ears.

Auditory attention tasks

The results show that Roger Focus II can help children with AP deficits even in quiet classrooms. They can be sitting 5 meters away and still hear the teacher at a high performance level. We can also see that when using Roger Focus II, speech intelligibility results in noise for children with AP deficits can be significantly better than their peers, who were not using Roger Focus II.

These findings might not be surprising. We know that children with AP deficits struggle with listening in background noise and at a distance4,5 and that Roger systems bring the microphone wearer’s voice directly to the child’s ears.

What is interesting is how much of a difference Roger Focus II can make for these kids. It isn’t always possible for the child to be sitting near the teacher and for the classroom to be quiet. When this isn’t possible, Roger Focus II can help reduce their difficulties hearing the teacher’s speech.

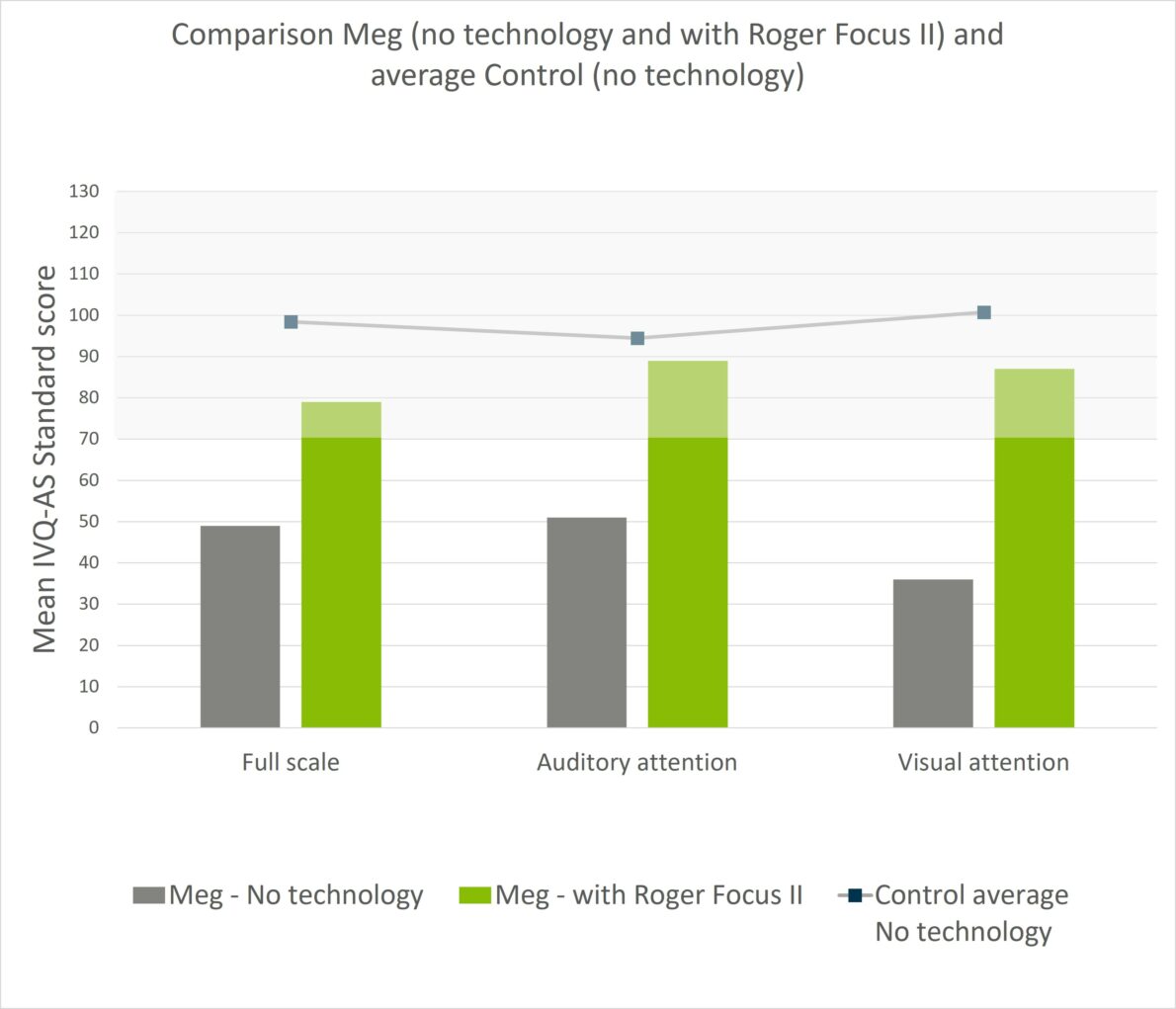

Visual attention tasks

Another interesting observation is the effect Roger Focus II has on auditory attention. For the case study presented, not only was auditory attention affected by distance and noise, so was visual attention. With Roger Focus II, performance in both auditory and visual attention tasks increased to within normal limits (shaded grey area). See Figure below.

Could Roger Focus II be of benefit for the children you see with a UHL or AP deficits either in the clinic or in your school? Based on these studies, the answer is Yes, it is worth a trial.

To learn more about Roger Focus II, we invite you to visit our webpages.

References

- Bagatto, M., DesGeorges, J., King, A., Kitterick, P., Laurnagaray, D., Lewis, D., Roush, P., Sladen, D. P., & Tharpe, A. M. (2019). Consensus practice parameter: audiological assessment and management of unilateral hearing loss in children. International Journal of Audiology, 58(12), 805–815. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2019.1654620

- Nelson, J. & Dunn, A. (2021). Roger Focus II in children with unilateral hearing loss. Phonak Field Study News. Retrieved from www.phonak.com/evidence, accessed January 2023.

- Nelson, J., & Shiels, L. (2022). Roger Focus II: A solution for auditory processing deficits. Phonak Field Study News. Retrieved from www.phonak.com/evidence, accessed January 2023. The peer review paper is currently in preparation.

- Lagacé, J., Jutras, B., & Gagné, J. P. (2010). Auditory Processing Disorder and Speech Perception Problems in Noise: Finding the Underlying Origin. American Journal of Audiology, 19(1), 17-25. https://doi.org/10.1044/1059-0889(2010/09-0022)

- Howard, C. S., Munro, K. J., & Plack, C. J. (2010). Listening effort at signal-to-noise ratios that are typical of the school classroom. International Journal of Audiology,49(12), 928-932. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2010.520036