Healthy hearing and healthy aging

Research suggests hearing loss may be associated with cognitive decline. As HCPs, what do we need to know about this risk and what part are we able to play in the awareness of this?

We all know that hearing is important. At a very fundamental level it is one of 5 major sensory inputs. Hearing enables our connection with the world through conversation, music and environmental sounds. When we lose our hearing, we run the risk of losing these connections.

Age-related hearing loss is a growing concern. The World Health Organization reports that 1/3 of the world’s population over 65 have hearing loss. A study by Chien et al. reported that in the US, the prevalence of hearing aid use in those aged 50 or over with a hearing loss, was 14.2%.1

Why is this a growing concern? Firstly, we all know that communication is the building block to connection, and a fundamental part of this is hearing. It has long been recognised that unaided hearing loss can increase the likelihood of social disengagement and poor quality of life. Secondly, there is growing data that those with hearing loss are at higher risk of cognitive decline 2 and co-incident dementia.3 Dementia is a global challenge with 47 million people living with dementia in 2015, with this number expected to triple by 2050 3 and hence there is a large push to identify risk factors throughout one’s lifetime.

What does hearing loss have to do with dementia?

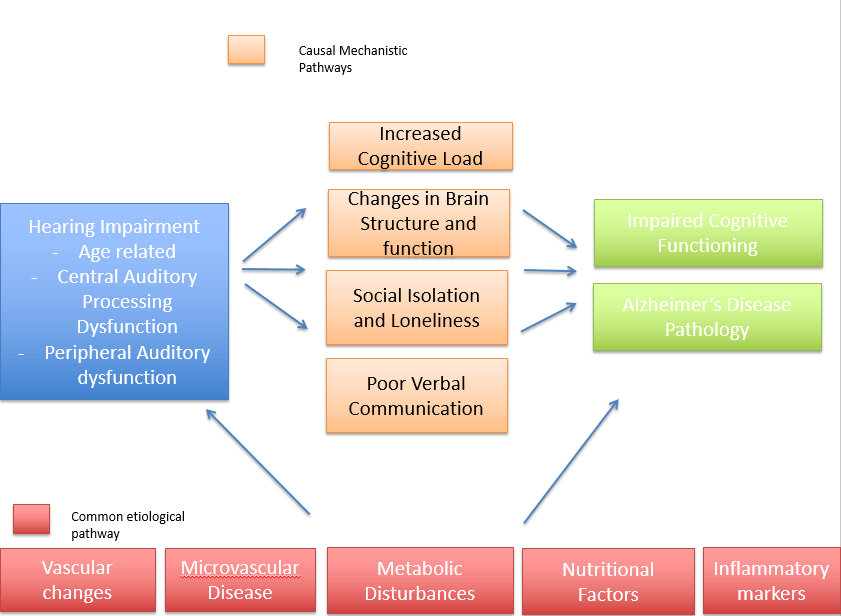

Awareness of the relationship between hearing loss and dementia is relatively new. Research from cohort studies demonstrate that even those with mild hearing loss are at a higher risk of developing cognitive decline or dementia relative to their normal hearing counterparts. 3,4,5 It has been suggested that auditory deprivation from hearing loss results in a higher cognitive load, which can increase ones’ susceptibility to cognitive decline.

Other proposed theories are that there is some common causal pathway with other etiologies that lead to the development of dementia. Proposed pathways are outlined in Figure 1.

Reducing the risk is possible

A recent report in The Lancet, by Livingston and colleagues, identified hearing loss as the greatest modifiable risk factor for dementia in midlife.3 Recognition of this risk will motivate individuals to be more proactive about their hearing health, with the aim of creating a movement to reduce the global impact of hearing loss.

Moreover, it is really important that people understand that the maintenance of social communication is integral in healthy aging, and that hearing aids can help significantly with this. An article by Barbara Timmer, a researcher at the University of Queensland, discusses the impact of mild hearing loss and why it shouldn’t be dismissed as unaidable.6 In this review, Barbara emphasizes that audiometry alone should not be relied on to determine whether hearing aids should be prescribed. Rather, that a true measure of someone’s hearing loss lies in a self-report of how they experience their hearing.6 This means that slight or mild losses should not be dismissed as unaidable if the client has concerns about their loss impacting their quality of life.

Three ways HCPs can make a difference

- Bringing in a more holistic understanding about the cognitive and social impact of hearing loss with our clients could help encourage them to be more proactive about their hearing loss. The more information they are given, the more empowered they are to make an educated decision about their hearing health.

- The way in which we as HCPs communicate this is also hugely important; if we can reduce the stigma by illustrating hearing aids as a powerful tool to enable a better of quality of life, undoubtedly there would be less resistance to the process as well as a reduction in time between diagnosis and action.

- Further, increasing awareness around the impact that hearing loss can have on one’s quality of life, as well as the purported risk factors, could reduce barriers in the uptake of hearing aids and the number of people living with unaided hearing loss.

By helping our clients understand the benefits of hearing well, we can facilitate healthy aging and enable great enjoyment of the ‘golden years.’

We invite you to read a previous blog post by Charlotte Vercammen, PhD, on what hearing rehabilitation can truly mean for an individual.

References

- Chien, W., & Lin, F. R. (2012). Prevalence of hearing aid use among older adults in the United States. Archives of internal medicine, 172(3), 292–293. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1408

- Lin, F. R., Ferrucci, L., Metter, E. J., An, Y., Zonderman, A. B., & Resnick, S. M. (2011). Hearing loss and cognition in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Neuropsychology, 25(6), 763–770. doi:10.1037/a0024238

- Livingston, G., Sommerlad, A., Orgeta, V., Costafreda., Huntley, J., Ames, D., Ballard, C., Banarjee., Burns, A., Cohen- Mansfield, J., Cooper, C., Fox., Gitlin., L.N., Howard, R., Kales., Larson, E.B., Ritchie., K., Rockwood, K., Sampson, E.L., Samus, Q., Schneider, LS., Selbaek, G., Teri., L., Mukadam, N., (2017) Dementia Prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet; 390: 2673-734

- Lin, F. R., Metter, E. J., O’Brien, R. J., Resnick, S. M., Zonderman, A. B., & Ferrucci, L. (2011). Hearing loss and incident dementia. Archives of neurology, 68(2), 214–220. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2010.362

- Deal, J.A., Betz, J., Yaffe, K., et al. for the Health ABC Study Group. (2016, April 12). Hearing impairment and incident dementia and cognitive decline in older adults: the Health ABC Study. The Journal of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. doi:10.1093/gerona/glw069.

- Timmer B. (2014). It may be mild, slight, or minimal, but it’s not insignificant. Hearing Review. 21(4):30-33.