Does audibility impact an older child’s performance on complex listening tasks?

A recent study looked at whether hearing aid programming can be changed for older children without significantly impacting their ability to complete complex auditory tasks. Researcher, Dr. Elizabeth Stewart provides a summary of the findings.

If you haven’t heard of the cognitive load theory (CLT)1 by name, you are likely at least familiar with it in concept, as it illustrates one of many reasons hearing loss is relevant to cognition on a broad scale.

The CLT hypothesizes that decoding an auditory signal degraded by hearing loss requires the recruitment of cognitive resources that would otherwise be used for other cognitive processes (e.g., working memory).

Recent study put this theory to the test

In collaboration with Phonak, a study conducted at Arizona State University yielded evidence regarding the relationship between audibility and performance on listening tasks that varied in cognitive demand in a group of 17 older children and teens (9-17 years old) with mild to moderate hearing loss.2

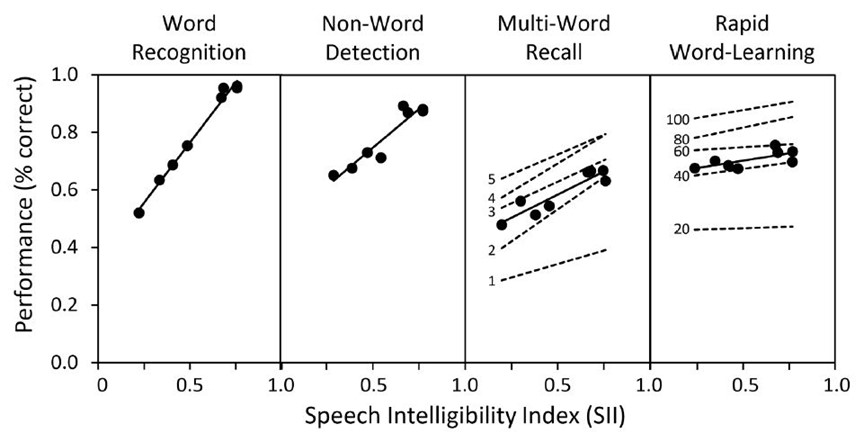

The test battery included four suprathreshold tasks representing increasing cognitive demand: word recognition, nonword detection, multiword recall, and rapid word learning. (See methodology section below for a brief description of each task).

Participants completed all tasks in four different hearing aid conditions, created by combining two different fitting formulas (DSL v5.0a, NAL-NL2) and two different Speech Enhancer settings (On at default, Off). The stimuli for each task were presented at low and high presentation levels (40 and 70 dB SPL, respectively).

Also, simulated real ear measures were completed by presenting task stimuli through a hearing aid analyzer (Verifit2) to calculate the speech intelligibility index (SII) for each participant, presentation level, and hearing aid condition.

Study results

The circles and solid lines in the figure represent performance for each level of SII for each task. Overall, these results revealed a diminishing relationship between SII and performance as the cognitive demand of the task increased.

For example, word recognition performance improved as expected as audibility increased. By contrast, performance on the rapid word learning task showed almost no change with increasing SII, even at the highest and lowest levels of audibility.

These results suggest that perception of familiar words is highly sensitive to signal audibility, while word recall and learning are less sensitive. In fact, the children and teens in this study were able to perform cognitively complex tasks fairly well with minimal amounts of audibility (0.20–0.29 SII).

Implications for practicing clinicians

What these findings mean in a practical context is that hearing care professionals can make changes to children’s hearing aid programming (for example, switching the fitting formula from DSL to NAL to improve listening comfort, and activating Speech Enhancer to provide additional clarity for soft speech) without significantly impacting their ability to complete certain complex auditory tasks.

The Test Battery

Word recognition: A common measure of speech understanding used clinically, this task consisted of lists of 20 monosyllabic words drawn from the Northwestern University (NU-6) word lists. Participants were instructed to repeat each word aloud; their verbal responses were recorded digitally and scored offline for accuracy.

Nonword detection: The stimuli for this task consisted of lists of 20 three-word phrases containing a mix of real and nonsense words; responses were recorded via an interactive computer game. Participants were instructed to indicate only the nonsense words by selected the correct numbered response button(s) corresponding to the position of each nonsense word in the phrase.

Multiword recognition: This task was adapted from the Auditory Verbal Learning Test, commonly used to assess episodic memory. Participants listened to five repetitions of a 14-word list and were instructed to repeat as many words as they could recall (in any order) following each repetition. The primary endpoint for this task was the total number of words correctly recalled, summed across all five trials.

Rapid word learning: In this task, participants learned to associate sets of 5 novel words with sets of 5 novel images via an interactive computer game and a process of trial-and-error. Participants were instructed to select one of the novel images after the presentation of each nonsense word. Reinforcement was provided if the participant correctly selected the image assigned to the nonsense word; no reinforcement was provided for incorrect selections. Each of the five nonsense words was repeated 20 times, in random order.

To access the full peer-reviewed article in Trends and Hearing, click here.

References

- Sweller, J., Ayres, P. H., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory. Springer.

- Pittman, A. L., & Stewart, E. C. (2023). Task-Dependent Effects of Signal Audibility for Processing Speech: Comparing Performance With NAL-NL2 and DSL v5 Hearing Aid Prescriptions at Threshold and at Suprathreshold Levels in 9- to 17-Year-Olds With Hearing Loss. Trends Hear, 27, 23312165231177509.