The teenage brain – Ready for advanced conversations

On a daily basis, teens contend with complicated problems and choices. Talking about complications can help!

As young parents and avid readers, my husband and I enthusiastically embraced the practice of reading to our children at every opportunity, especially at bedtime. Because it was just plain fun, we kept up the routine for years, until the kids reached 14.

We worked our way through chapter books, from “young reader lit” to advanced material like Dickens’ A Christmas Carol and Tolkien’s The Hobbit (not a personal favorite).

Of all the books we tackled, my strongest memories relate to Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Why? Because the themes of the book – racism, moral hypocrisy, loyalty, journeying – had to be addressed with sidebar conversations for almost every page.

We needed to explain why Mark Twain chose to use terminology that we as a family would never utter. We would pause to wonder, what would we do if we were Huck, and why? It was intense! By the time we reached the pivotal moment when Huck decided not to betray his beloved friend Jim, I didn’t have to explain why his courage brought me to tears.

Teen brains undergoing a remarkable growth spurt

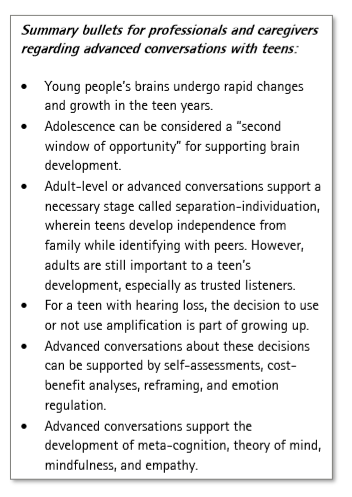

Unbeknownst to us at the time, these kinds of advanced conversations support brain development. We now know that a second spurt of brain growth begins around the age of 9 and continues through the teen and young adult years (or as UNICEF [2017] describes this stage, a “second window of opportunity”).

All growing organisms need food, and the brain is no exception: in this case, “food” involves new information, complex topics, and cognitive challenges. The consideration of advanced topics stimulates neural activity; serious conversations about these topics can help organize random neural activity into fused neural networks (Seigel, 2015).

Like every other life skill, teens need practice

Advanced conversations about moral dilemmas, societal values, or choices and consequences do not arise only from books or school coursework. The world is full of complex topics. Today’s teens contend with advanced problems and choices on a daily basis; when a teen has a hearing loss, one of the choices may involve using amplification.

The following are four ways HCPs can approach advanced conversations when discussing a teen’s decision to use or not use amplification.

- Self-assessments – Tools such as the Self-Assessment of Communication – Adolescent (SACA) can be used as a springboard for discussion.

- “Cost/benefit” analysis – Advanced conversations about amplification can be framed in terms of costs and benefits to help teens consider all sides of the decision.

- Reframing – By changing our language during advanced conversations, we can help reframe their thoughts when situations are viewed in extreme ways (only good/bad, never/always, all or none) .

- Discuss books – Discussing books that involve “big decisions” can facilitate advanced conversations regarding amplification.

It’s a complicated issue – so let’s have an advanced conversation about it!

To learn more about teen brain development, see the Phonak Insight paper, The amazing teenage brain: Ready for advanced conversations.

References:

Siegel, D.J. (2015). Brainstorm: The power and purpose of the teenage brain. NY: Penguin Random House.

UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti. (2017). The adolescent brain: A second window of opportunity. Innocenti, Florence: UNICEF. Retrieved February 8, 2019: https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/933-the-adolescent-brain-a-second-window-of-opportunity-a-compendium.html