Listening-related fatigue, well-being and the importance of daily-life activity

Researcher, Dr. Jack A. Holman shares his learnings on how listening-related fatigue can impact well-being.

We know that hearing loss can contribute to a range of problems for people in everyday life, and each problem could reduce that person’s happiness, comfort, health or self-worth: their well-being.

To tackle this, we can first try to understand in more detail how each problem affects well-being.

Listening-related fatigue

On the third hour of video-calls you can be forgiven for feeling tired and wanting to switch off. This listening-related fatigue is your brain’s way of telling you that the effort outweighs the rewards and that your attention is better off focused elsewhere,1 sorry colleagues!

Hearing loss takes the effort/reward trade off that everyone experiences in daily-life listening situations and tips the balance towards exhaustion.

Positive well-being is achieved if the challenges someone faces are sufficiently handled by their inner resources.2 Unsurprisingly, sustained severe fatigue negatively impacts well-being.3,4 It is believed that hearing loss increases an individual’s susceptibility for severe listening-related fatigue, and hearing device use can be beneficial.5

But susceptibility to listening-related fatigue in a hypothetical challenging situation would not necessarily equate to the real-life impact on well-being as it does not take account of daily life activity.

Two people could be equally susceptible to listening-related fatigue, but they may face very different listening situations. While one might work full-time and have an active social life, the other might spend all of their time in quiet situations at home.

So, what impact does hearing loss have on daily-life activity, and what is the role of activity in listening-related fatigue and well-being? We had a look at the available evidence.

Social activity

- Research shows that, for the elderly in particular, hearing loss is linked to reduced levels of social activity.6 Hearing loss also makes social situations more challenging and potentially less enjoyable. This is important as it seems that the enjoyment and control one has in social situations dictates the level of fatigue.7,8 So, a person’s well-being would likely be affected by both listening-related fatigue and sub-optimal social activity.

- Hearing device use on the other hand is linked to increased social activity.9 So, as long as the social activity is enjoyed, fatigue should lessen, and well-being should improve.

Work activity

- All things being equal, people with hearing loss are more likely to be unemployed and possibly even to retire early.10 The key factor when it comes to how this affects fatigue is the reason behind the lack of work.

- Because of the associated pressures like job seeking, unemployment has been linked to increased fatigue.11 However, work itself can be tiring as we all know. The work demand and responsibility are likely key to how much fatigue is felt during work.12

- Retirement is usually a positive thing that a person has a lot of control of, and as such it is linked to decreased fatigue.13

- Cochlear implantation seems to help people get jobs,14 but the evidence for hearing aid fitting is less clear.

- A positive change in employment status would undoubtedly improve well-being, and any on-the-job fatigue could be seen as an improvement on the fatigue caused by the stresses of job-seeking.

Physical activity

- Hearing loss is linked to inactivity.15 Physical activity has no effect on listening-related fatigue of course, but reduced physical activity does increase feelings of general fatigue.16 This is important here as it has been argued by some that different types of fatigue (e.g. cognitive, emotional, physical) may in fact reflect one core concept of general fatigue.17

- Both fatigue and inactivity can negatively impact an individual’s well-being,18,3 so there could be an additive effect when someone has hearing loss.

So what does this mean?

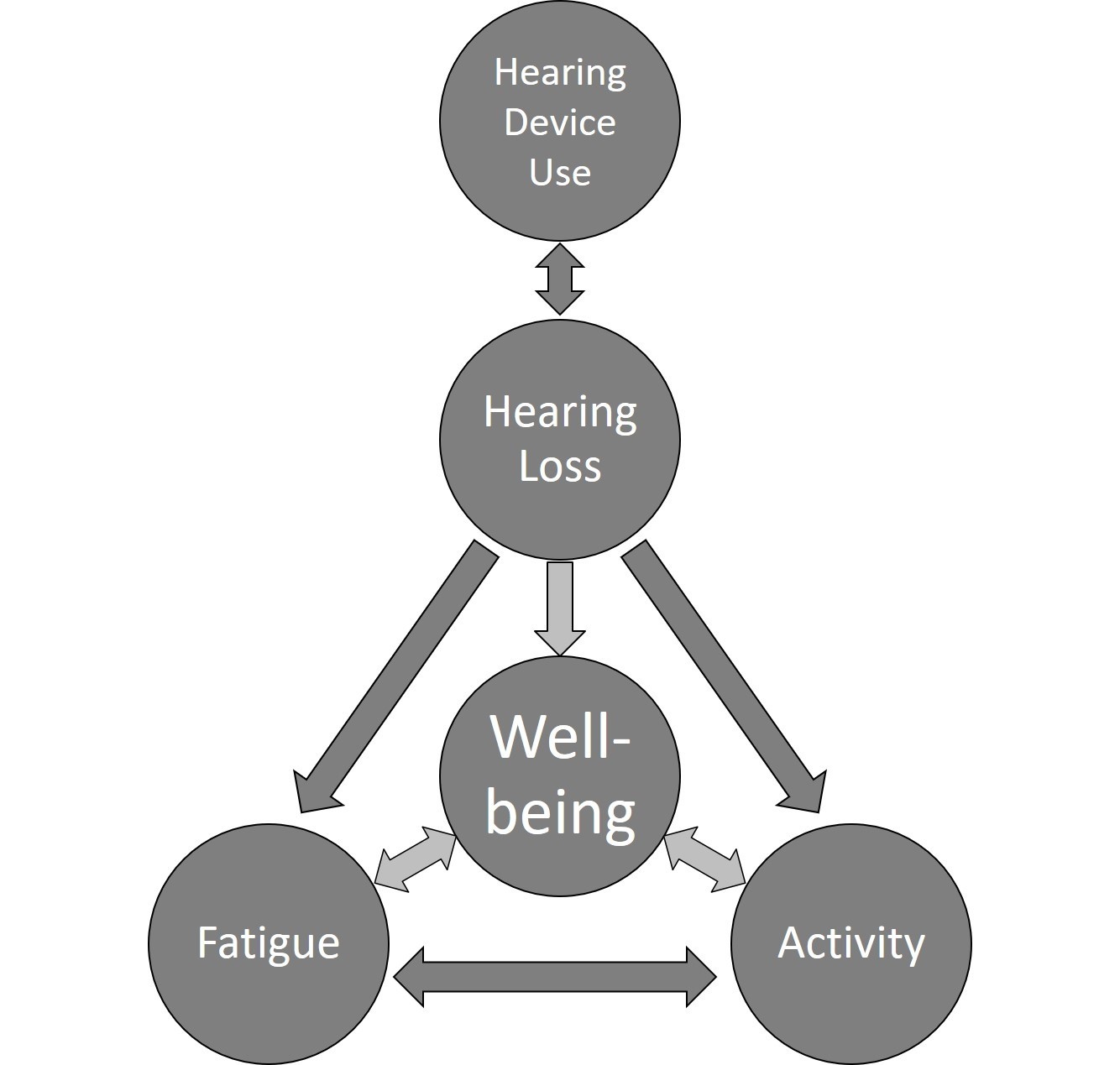

This evidence is clearly part of a complex picture! An individual’s hearing ability can directly influence their feelings of fatigue, their daily-life activity and their well-being. However, listening-related fatigue, activity and well-being are all interlinked; each has an impact on the other.

If you have skipped to the end of this article, here are some take-home messages:

- Regarding listening-related fatigue, consideration must be given to the daily life activity of each individual.

- If a person with hearing loss does not find themselves in fatiguing situations, then understanding why they are not in those situations may be the key to improving well-being.

- This research focused on listening-related fatigue, but the role of activity in the well-being of people with hearing loss is important in its own right.

For a more detailed insight into the relationships between listening-related fatigue, well-being and daily-life activity for people with hearing loss, you can read the full article via this link.

You can also find this and other articles dedicated to well-being topics in the IJA special supplement.

References:

- Hockey, R. (2013). The Psychology of Fatigue: Work, Effort and Control. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dodge, R., Daly, A. P., Huyton, J. & Sanders, L. D. (2012). The challenge of defining wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing; 2(3): 222–235. doi:10.5502/ijw.v2i3.4.

- Haack, M., & Mullington, J. M. (2005). Sustained sleep restriction reduces emotional and physical well-being. Pain; 119 (1-3): 56–64. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.011.

- Smith, A. P. (2018). Cognitive fatigue and the well-being and academic attainment of university students. Journal of Education, Society and Behavioural Science; 24 (2): 1–12. doi:10.9734/JESBS/2018/39529

- Hornsby, B. W. (2013). The effects of hearing aid use on listening effort and mental fatigue associated with sustained speech processing demands. Ear and Hearing; 34 (5): 523–534. doi:10.1097/AUD.0b013e31828003d8.

- Liljas, A. E. M., Wannamethee, S. G., Whincup, P. H., Papacosta, O., Walters, K., Iliffe, S., Lennon, L. T., et al. (2016). Hearing impairment and incident disability and all-cause mortality in older British community-dwelling men. Age and Ageing; 45 (5): 661–666. doi:10.1093/ageing/afw080.

- Oerlemans, W. G. M., Bakker, A. B. & Demerouti, E. (2014). How feeling happy during off-job activities helps successful recovery from work: A day reconstruction study. Work & Stress; 28: 1–216. doi:10.1080/02678373.2014.901993.

- Ten Brummelhuis, L. L., & Trougakos, J. P. (2014). The recovery potential of intrinsically versus extrinsically motivated off. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology; 87 (1): 177–199. doi:10.1111/joop.12050.

- Sawyer, C. S., Armitage, C. J., Munro, K. J., Singh, G. & Dawes, P. D. (2019). Correlates of hearing aid use in UK adults: Self-reported hearing difficulties, social participation, living situation, health, and demographics. Ear and Hearing; 40 (5):1061–1068. doi:10.1097/AUD.0000000000000695

- Helvik, A. S., Krokstad, S. & Tambs, K.(2013). Hearing loss and risk of early retirement. The HUNT Study. The European Journal of Public Health; 23 (4): 617–622. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cks118.

- Lim, V. K. G., Chen, D., Aw, S. S. Y. & Tan, M. (2016). Unemployed and exhausted? Job-search fatigue and reemployment quality.” Journal of Vocational Behavior; 92: 68–78. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2015.11.003.

- Åkerstedt, T., Knutsson, A., Westerholm, P., Theorell, T. Alfredsson, L., & Kecklund, G. (2004). Mental fatigue, work and sleep. Journal of Psychosomatic Research; 57 (5): 427–433. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2003.12.001.

- Westerlund, H., Vahtera, J., Ferrie, J. E., Singh-Manoux, A., Pentti, J., Melchior, M. Leineweber, C. et al. (2010). Effect of retirement on major chronic conditions and fatigue: French GAZEL Occupational Cohort Study. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.); 341: c6149. doi:10.1136/bmj.c6149.

- Clinkard, D., Barbic, S., Amoodi, H., Shipp, D. & Lin, V. (2015). The economic and societal benefits of adult cochlear implant implantation: A pilot exploratory study. Cochlear Implants International; 16 (4):181–185. doi:10.1179/1754762814Y.0000000096.

- Chan, Y. Y., Sooryanarayana, R., Mohamad Kasim, N., Lim, K. K., Cheong, S. M., Kee, C. C., Lim, K. H., Omar, M. A., Ahmad, N. A., & Mohd Hairi, N. N.. (2019). Prevalence and correlates of physical inactivity among older adults in Malaysia: Findings from the National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2015. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics; 81: 74–83. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2018.11.012.

- Ishizaki, Y., Ishizaki, T., Fukuoka, H., Kim, C.-S., Fujita, M., Maegawa, Y., Fujioka, H. et al. (2002). Changes in mood status and neurotic levels during a 20-day bed rest. Acta Astronautica; 50 (7): 453–459. doi:10.1016/S0094-5765(01)00189-8.

- Michielsen, H. J., De Vries, J., Van Heck, G. L., Van de Vijver, F. J. R. & Sijtsma, K. (2004). Examination of the dimensionality of fatigue. European Journal of Psychological Assessment; 20 (1): 39–48. doi:10.1027/1015-5759.20.1.39.

- McAuley, E., Blissmer, B., Marquez, D. X., Jerome, G. J., Kramer, A. F. & Katula, J. (2000). Social relations, physical activity, and well-being in older adults. Preventive Medicine; 31 (5): 608–617. doi:10.1006/pmed.2000.0740.