Hyperacusis treatment: Insights from a 6-month field trial

A group of audiologists, engineers and hearing scientists developed a novel treatment device and protocol that significantly improved participants’ sound sensitivity and quality of life.

“Everything is too loud”

“It is affecting my relationships and hobbies”

“I’m isolating myself more and more”

These are common statements made by individuals with hyperacusis. But how can novel technology and clinical practice help?

Understanding hyperacusis and the Catch-22 dilemma

Hyperacusis is an intolerance to the loudness of everyday sounds that aren’t bothersome to the general population. Literally, “hyper-” means excessive and “-acusis” means sound perception.

This inability to tolerate loud sounds can result in a decreased dynamic range, avoidance of noisy environments, and excessive use of hearing protection. These strategies can severely limit social interaction and have a negative impact on quality of life.

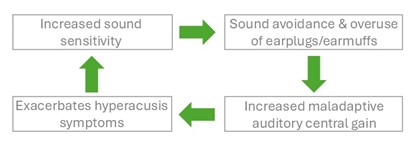

Individuals with hyperacusis typically present in clinics wearing sound-attenuating earplugs and/or earmuffs for comfort and protection against offending sound. However, research shows that long-term use of sound attenuators may “turn up” the gain in central auditory pathways, further worsening sensitivity.1-3 This sets up a Catch-22 dilemma: patients overuse sound attenuators to manage symptoms, but doing so may intensify them.4

What current literature supports

In addition to managing any comorbid conditions, the literature provides support for various intervention strategies:

- Counseling about the condition and appropriate use of hearing protection, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with a psychologist familiar with sound sensitivity or chronic pain.

- The online Hyperacusis Activities Treatment program.

- Sound therapy to provide exposure to healthy low-level sound to gradually reset abnormally high auditory gain through the brain’s natural adaptive process.

However, a clinical challenge remains: How can we safely support patients who are highly reliant on sound protection in transitioning to more sound-enriching environments? This is a critical step in recalibrating auditory system gain and restoring normal sound tolerance.

Insights from our research study

Our study treatment5 included a detailed counseling protocol, and a novel treatment device that acted as a successful transitional tool to replace maladaptive hearing protection.

The counseling protocol6 covered the following:

- Review of audiometric results.

- Overview of peripheral auditory structures and central auditory system.

- The concept of central auditory gain.

- Maladaptive neural processes leading to hyperacusis; overuse of hearing protection exacerbating the condition; non-auditory processes contributing to negative emotional and physical reactions to sound.

- Sound therapy as a tool to down-regulate the hyper-gain activity.

The treatment device7 was a behind-the-ear slim-tube device with interchangeable earmolds and domes (Patent:8) that included the following:

- Loudness suppression (LS) feature, replacing earplugs, with the output limit set based on participants’ judgement of Category 6 “Loud but Ok” from the Contour test of loudness.9

- Low-level broadband sound therapy via sound generator (SG) in the devices.

- “Closed” in-the-canal custom earmold with a heat-activated expanding stent to achieve LS and SG treatment together, and an “open dome” to achieve SG treatment while allowing for healthy environmental sound exposure without LS.

- Unity gain algorithm (accomplished by matching participants’ Real Ear Occluded Response (REOR) to their Real Ear Unaided Response (REUR)) to compensate for the attenuation from the occluding earmold.

Participants were instructed to use the open dome when LS was not needed, promoting gradual reduction in reliance on attenuation.

Over the 6-month period:

˃ Participants had an average improvement of ~34 dB in the output-limiting LS setting (an average improvement of 5.6 dB at each visit).5

˃ Sound tolerance improvements were reflected in validated questionnaires.

˃ Participants gradually decreased their reliance on hearing protection and preferred to use the open dome with SG, rather than the closed mold with SG and LS.

˃ This transitional intervention had a positive improvement in many participants’ quality of life.

Clinical takeaways

Integrating LS into clinical treatment protocols offers a promising way to overcome the Catch-22 of hyperacusis treatment. By replacing maladaptive plasticity with therapeutic plasticity, clinicians can guide patients toward recovery without triggering discomfort, offering an opportunity to improve well-being and quality of life for individuals severely impacted by hyperacusis.

Recommendations for clinicians: A diagnostic test battery

- Allocate an appropriate amount of time for a thorough case history before escorting the patient to the sound booth.

- Include one or more questionnaires (e.g. Hyperacusis Questionnaire10).

- Perform tympanometry without acoustic reflex testing.Perform full audiometric testing. Use an ascending method for pure tone and speech testing with shorter speech lists. Use a 1- or 2-dB step size when the dynamic range is very small.

- Perform loudness discomfort level (LDL) testing with appropriate instructions at a minimum of two frequencies (one low frequency and one high frequency).

- Perform Contour Test loudness judgments (Cox et al., 1997) up to Category 6 of “Loud but Ok” at mid-frequency.Refer for medical and neurological evaluation to rule out or treat common comorbid conditions.

- Refer for hyperacusis treatment with a trained audiologist.Refer to a psychologist trained in CBT or chronic pain.

Acknowledgment:

This research was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

References:

- Formby, C., Sherlock, L.P., and Gold, S.L. (2003). Adaptive plasticity of loudness induced by chronic attenuation and enhancement of the acoustic background. J Acoust Soc Am, 114, 55–58.

- Baguley, D. M., and Andersson, G. (2007). Hyperacusis: Mechanisms, Diagnosis, and Therapies. Oxford, UK: Plural Publishing.

- Munro, K. J., Turtle, C., and Schaette, R. (2014). Plasticity and modified loudness following short-term unilateral deprivation: evidence of multiple gain mechanisms within the auditory system. J Acoust Soc Am, 135, 315–322.

- Vernon, J. A., and Meikle, M.B. (2000). Tinnitus Masking. In Tyler, R.S. (Ed.), Tinnitus Handbook (pp. 313–356). San Diego, CA: Singular.

- Formby, C., Cherri, D., Secor, C. A., Armstrong, S., Juneau, R., Hutchison, P., & Eddins, D. A. (2024). Results of a 6-month field trial of a transitional intervention for debilitating hyperacusis. J Speech Lang Hear Res, 67(6), 1903–1931.

- Cherri, D., Formby, C., Secor, C. A., & Eddins, D. A. (2024). Counseling protocol for a transitional intervention for debilitating hyperacusis. J Speech Lang Hear Res, 67(6), 1886–1902.

- Eddins, D. A., Armstrong, S., Juneau, R., Hutchison, P., Cherri, D., Secor, C. A., & Formby, C. (2024). Device and fitting protocol for a transitional intervention for debilitating hyperacusis. J Speech Lang Hear Res, 67(6), 1868–1885.

- Eddins, D. A., Formby, C. C., & Armstrong, S. W. (2020). U.S. Patent No. 10,582,286. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

- Cox, R. M., Alexander, G. C., Taylor, I. M., & Gray, G. A. (1997). The Contour Test of loudness perception. Ear Hear, 18(5), 388–400.

- Khalfa, S., Dubal, S., Veuillet, E., Perez-Diaz, F., Jouvent, R., & Collet, L. (2002). Psychometric normalization of a hyperacusis questionnaire. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec, 64(6), 436–442. https://doi.org/10.1159/000067570

Biography:

Dr. Dana Cherri is a licensed clinical audiologist and a hearing researcher who recently completed a clinical fellowship in the Department of Otolaryngology at the University of South Florida and is now an audiological researcher at Sonova AG. She received her BSc degree in Audiology from the American University of Beirut in Lebanon, and her PhD degree from the University of South Florida. Her clinical and research interests include auditory rehabilitation, hearing aid fitting and benefit assessments, tinnitus and hyperacusis treatment, and ecological momentary assessment.

Dr. Carrie Secor is a licensed clinical audiologist and currently a research audiologist at the University of South Florida. She completed her AuD degree at the University at Buffalo and has been pursuing research and clinical practice for more than 20 years. She has practiced at The Cleveland Clinic, Wade Park VAMC and other large hospitals, Universities, and non-profit settings. Her interests include amplification, cochlear implants, central auditory processing, aural rehabilitation, tinnitus and hyperacusis.

Dr. David Eddins is a certified clinical audiologist and a Professor at the University of Central Florida. He is a fellow of the Acoustical Society of America and of the American Institute for Medical and Biological Engineering. His work investigates the impacts of aging on hearing, communication, cognition, balance, and the study of voice quality perception. His research includes hearing enhancement and protection using various technologies such as ear-worn devices, the use of augmented acoustic environments, and quantification of deficit and benefit via ecological momentary assessment, tinnitus and hyperacusis.